For several years now, the LRF has been supporting the conservation efforts of African Parks (AP) in the Chinko wilderness of eastern Central African Republic (CAR). More recently, the LRF has also funded work of Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) in northern CAR. As LRF Director, it’s critical to visit as many of the sites that we support as possible to assess the impact of our grantees’ work and see how best our funding can further conservation efforts. I had never been to CAR before; it’s always been a place of mystery and wonder to me. So it was with great excitement that I set off to the heart of Africa.

Like anywhere in Africa outside of Southern and East Africa, travelling to CAR from my home in Zimbabwe takes a lot of effort. Flying via Nairobi and Entebbe, I finally reached the capital Bangui buzzing with a sense of anticipation. CAR is often in a state of civil conflict, and as a result, the capital has not benefited from the kind of development that other major African cities have seen. Since independence in 1956, ongoing wear and tear has not been kind to Bangui and the streets are littered with potholes and lined with stalls selling goods of all kinds. Notable was the abundance of wild meat, known as bushmeat, being sold in plain view. This is an uncommon sight in most of Southern and Eastern Africa, as the sale of bushmeat is regulated and driven underground.

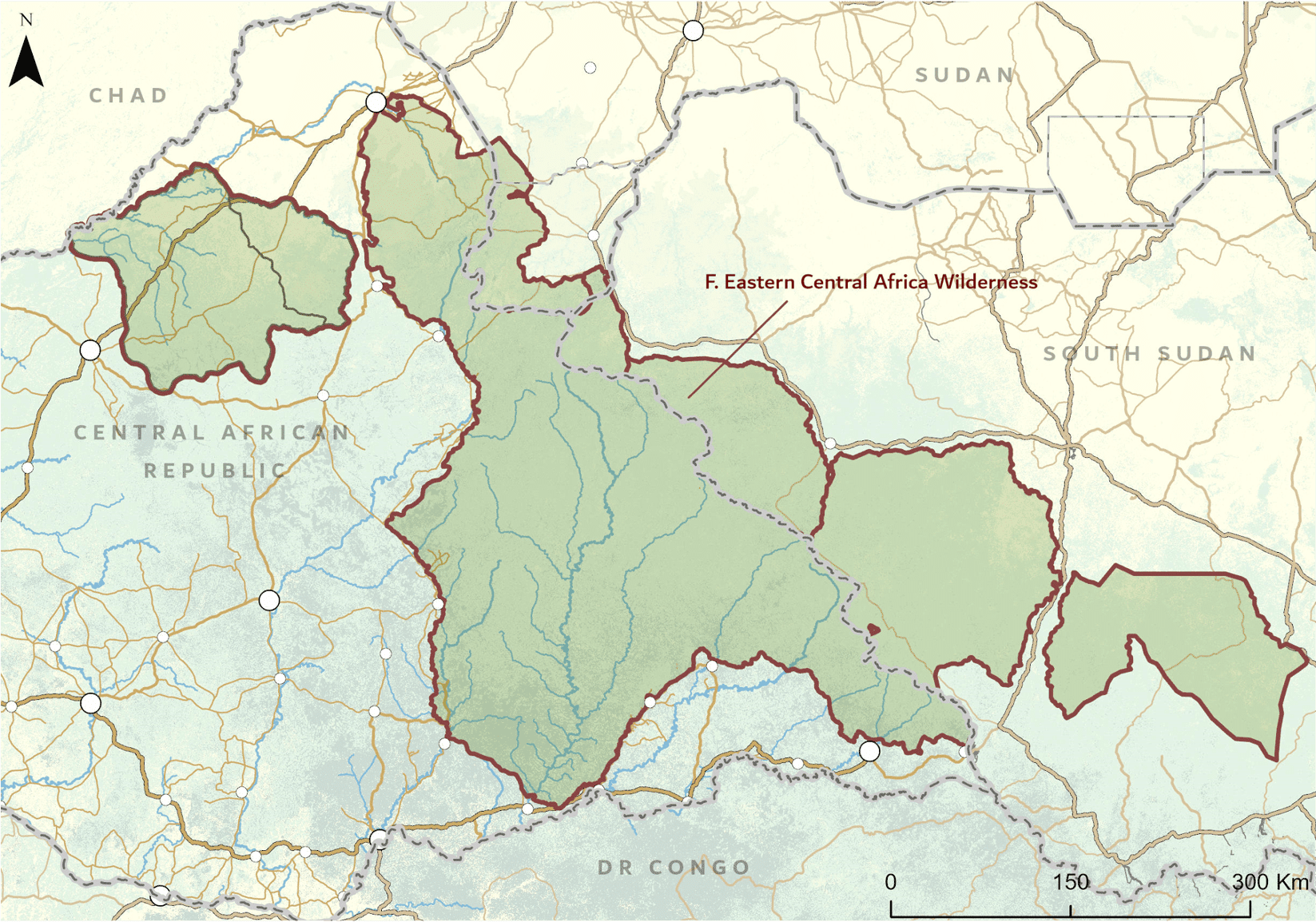

WCS works in northern CAR, and their project site was the first stop on the tour. WCS manages a vast swathe of wilderness of over 38,600 sq. miles, which includes Bamingui-Bangoran National Park, Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park, and a number of hunting areas in-between. AP works in the east of the country, managing an area of 25,000 sq. miles, referred to as the Chinko conservation area. Travelling to these areas required long flights in a Caravan aircraft. These flights emphasised just how much space and wilderness remains in CAR. During 3.5 hours of flying over northern and eastern CAR, the only signs of human development that we saw were two dirt roads and one small settlement.

CAR is an anomaly in Africa in that it receives high rainfall, is fertile, and yet has a very low human population density. The vast open spaces create incredible opportunities for conservation and make CAR one of Africa’s most exciting countries from a natural perspective. However, the country’s insecurity and limited infrastructure create major challenges. Driving to Chinko from Bangui takes a week with a 4×4 pickup, and supply trucks take no less than three weeks and risk possible attack by armed groups along the way.

Wildlife in CAR has suffered a difficult time over the last three decades. In the 1980s, armed Janjaweed poachers from Sudan killed a lot of wildlife. Travelling with donkeys, these poachers caused two rhino species to go locally extinct, killed vast numbers of elephants for their ivory, and targeted other wildlife for various body parts and bushmeat. This caused a major collapse in wildlife populations across northern and eastern CAR.

Wildlife enjoyed a brief period of recovery until the early 2000s, when CAR started to experience major influxes of nomadic livestock herders from neighbouring countries. Previously, nomads largely avoided CAR and stuck to drier areas to the north due to the prevalence of trypanosomiasis, carried by the tsetse fly. However, with the increasing availability of drugs used to treat trypanosomiasis, nomads began leading their cattle into CAR. In addition, when Sudan split into Sudan and South Sudan, it rendered the latter unavailable to many herders from the north, forcing them to seek alternative pastures in CAR. The influx of herders and hundreds of thousands of cattle resulted in a second major collapse in wildlife populations as some herders poisoned carnivores to protect their cattle and shot massive numbers of animals for food and to ship bushmeat to markets. The result was vast, near-empty savannah, the near extinction of kob antelope and giraffes in CAR, and a drastic reduction in lion and elephant numbers throughout much of the country.

A turning point came in the late 2000s, when local conservationists approached African Parks to see if they might be interested in taking on the Chinko region as a conservation project. AP agreed to do just that, eventually signing a management mandate for the area that was subsequently expanded to incorporate an area seven times larger than Yellowstone National Park. This resulted in a major injection of capital and conservation expertise, as well as a concerted effort to bring threats to wildlife under control. This meant investing in law enforcement and working closely with the nomadic herders.

Eastern CAR is incredibly biodiverse because it encompasses Sudano-Guinean savannah, gallery forests, and true Congolian rainforest. As a result, Chinko contains both savannah and forest biodiversity. Iconic savannah species include wild dogs, giant eland, and lions, while key forest species include bongo antelope, giant forest hogs, and chimpanzees. The area contains eight species of duikers, nine species of mongooses, and four pangolin species. Eastern CAR was so poorly studied that many species were not known to be present here until recently.

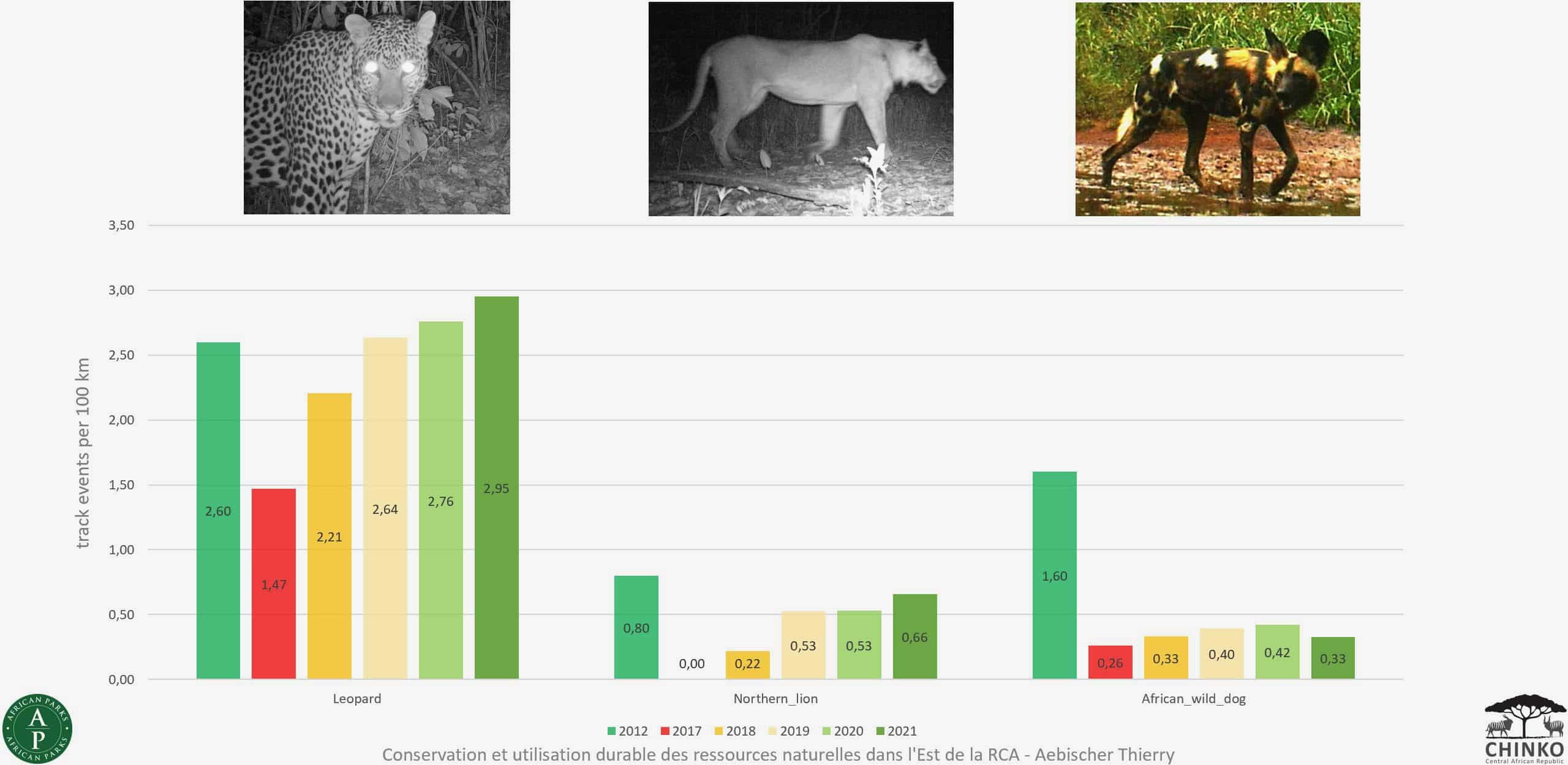

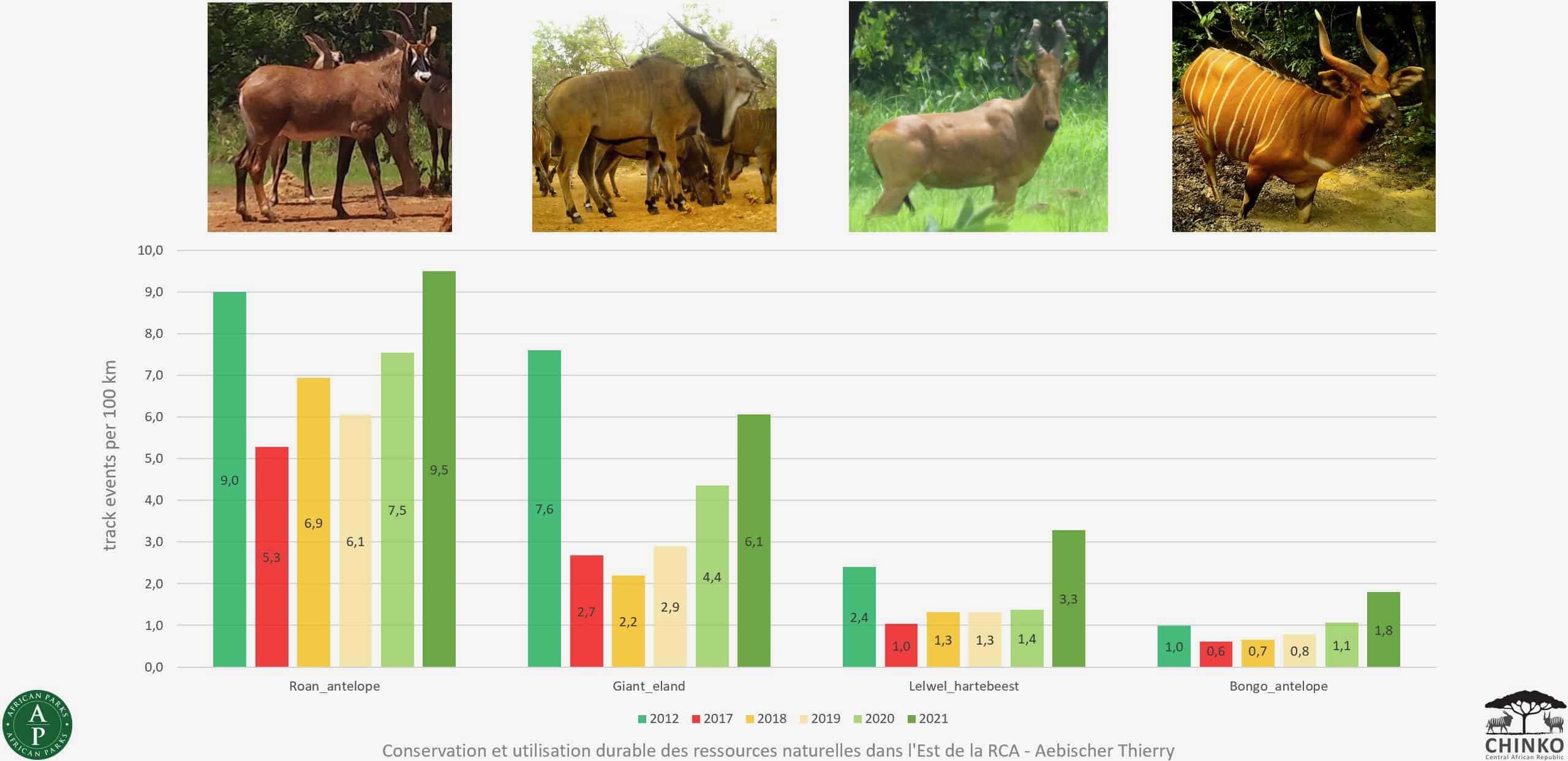

Wildlife has responded remarkably to protection. During 2012-2017, which were the peak years of nomadic pastoralism in Chinko, all large herbivores and carnivores declined steeply in number. From 2017, things started to turn around and now wildlife is increasing rapidly. Chinko now contains an estimated 4,000 buffalo, increasing by approximately 20% per year. There are at least 2,500 bongo, which is likely the largest protected population in Africa, and perhaps 2,500 chimpanzees. There are 1,500 giant eland, which are growing in number and which, if not already, will soon comprise the largest remaining population in Africa. Additionally, Chinko houses at least 100 wild dogs and about 100-150 lions. However, that number is set to grow rapidly.

Together, eastern and northern CAR comprise a truly vast wilderness. While I have dwelt largely on the Chinko area because AP’s project is more established, there is no reason why WCS cannot achieve similar successes in the protected areas of northern CAR as their recently initiated work gathers momentum. Overall, in CAR and the edges of neighbouring states there is an area of 77,000 sq. miles—nearly twice the size of Tennessee—with virtually no human settlement. This vast space is one of the regions of the world least affected by light pollution and creates incredible opportunities for nature conservation. To the east lies the massive Southern National Park in South Sudan, to the south lies the Bili-Uere Reserve in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and to the north lies Zakouma National Park and other protected areas in Chad. This long-neglected area is now starting to receive real conservation attention from multiple NGOs. Fauna and Flora International are working in Southern NP to support the wildlife authorities there, African Wildlife Foundation are working in Bili-Uere, AP in Chinko and Zakouma, and WCS in the northern parks in CAR.

The benefits of conservation in CAR are not just limited to wildlife. Eastern CAR is the source of seven major rivers, including the Congo River and those that flow into Lake Chad. Chinko is the largest employer and tax payer in eastern CAR, and the area is an island of peace in a very unstable region. Over 300 refugees (mainly women and children) sought refuge in Chinko, fleeing from massacres in their hometowns, where they were housed and fed by AP before returning home. That is, minus the 30 refugees who became permanently employed in Chinko.

Large scale conservation and land use planning can ensure that the natural heritage of CAR is retained, that future potential for tourism and the sale of carbon credits is retained, and that watersheds are protected. Properly managed pastoralism can also thrive, and with land use planning can be undertaken without the desertification associated with overgrazing that has been seen in other parts of the Sahel. Well-managed conservation areas can contribute to the maintenance of peace and stability, which is an essential prerequisite to human well-being.

Circling back to lions, eastern CAR has more potential for lion recovery than any other place in Africa. This region could essentially secure the future of the northern subspecies of lion. In addition, eastern CAR could become a critical stronghold for the four African pangolin species, wild dogs, bongos, giant eland, and many other species. The system could become a critical source of wildlife to restock depleted conservation areas elsewhere in Central and West Africa. To achieve this objective, there is a need for land use planning, for collaboration among conservation groups, for scaling up the successes achieved by African Parks, and the investment of substantial funding. To this end, the LRF has invested one of our largest grants to support AP’s work in Chinko and has invested heavily in Zakouma. The LRF has also helped kick-start work of WCS in northern CAR and is supporting FFI’s work in South Sudan. With your help, we can continue supporting efforts to restore this glorious wilderness and save the northern lion.