Like so many lions, he just appeared with his brother—in the middle of Gudigwa Village. It was early March and the villagers were understandably terrified. We received a call and jumped in a government vehicle with our colleagues from the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP) to assess the situation and determine what options were available. We were met with a community that was scared, frustrated, and wanted action. We approached the cats with the vehicle to try to encourage the lions to move on, but they would not budge. We contacted Department of Wildlife Veterinarians, private veterinarians, and other transport systems to help us move the lions, but nobody was available. Since DWNP had to return their vehicle to their office, we had to leave as well.

The next morning, we returned to find that the lions had killed a cow in the night. As we spoke to the woman present at the affected homestead, she mentioned that her husband and sons had followed the tracks from the kill with rifle in hand. They were on the hunt. We needed to intercept them before they encountered the lions. Sometimes these lion hunts end with an injured or dead person. Then we saw the men walking toward the vehicle. They had nearly reached the lions, but abandoned the hunt when they received word that we were coming. They were angry about the dead cow and wanted some assistance. We helped file a conflict report that would provide full compensation from the Botswana government. We pressed on.

We finally got a visual on the two young males. They were about three years old. A formidable size, but still roaming on the margins without a territory—hoping not to encounter the territorial male. We called veterinarian Dr. Rob Jackson, as well as some friends from Helicopter Horizons to help us with the situation. Our plan was to dart and release these lions just outside of the village in hopes of avoiding further losses. By the time the helicopter arrived, we were fighting the sinking sun. The lions were shy and stayed hidden to avoid being darted from above. Finally, Rob got his shot and hit one of the males. The other male ran. We came in on the ground and fitted the male with a collar. We did not want to separate the males, but we also did not want to leave one alone in the village. Our colleague from DWNP instructed us to translocate the one in hopes that he would lure the other away from the village. With little light remaining, we followed instructions, releasing the male about 30 miles from the area—not too far for the lions to reunite.

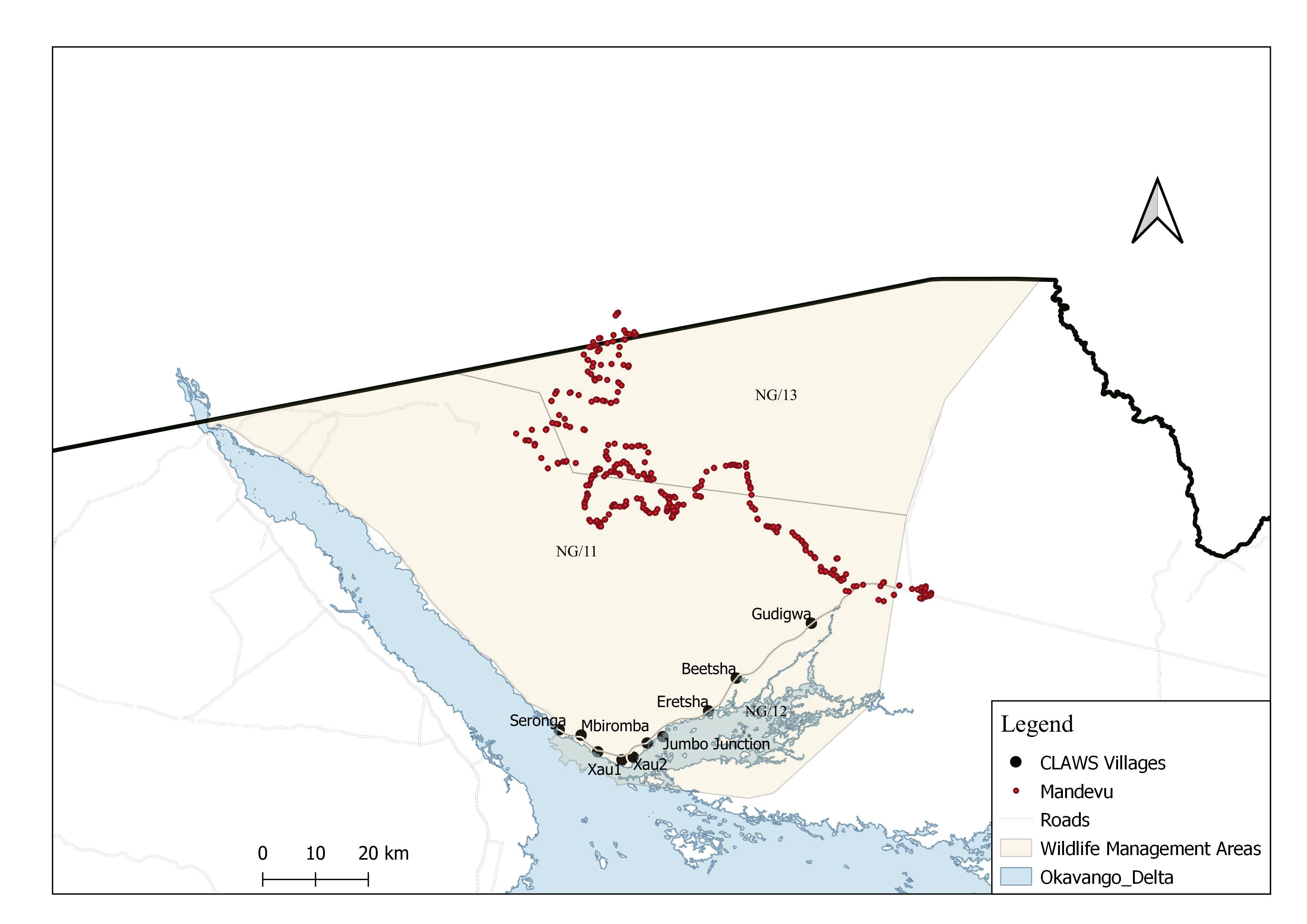

But the story wasn’t over for these lions. After regrouping, they continued further north, crossing the border into Namibia (the black border line on the map above). We contacted our colleague, Lise Hanssen from the Kwando Carnivore Program, who is studying predators in this region of Namibia, to help us monitor these lions. When she saw the map of their location, she gave us the news. These lions were in an area of dense livestock farming and very intolerant farmers. Lions are shot here regularly. They are in trouble, especially having tasted cattle already. We are monitoring Mandevu’s movement patterns in hopes that he will return to Botswana without incident. Our collar is still working, so we are optimistic.

In the meantime, we have collected some valuable information about lion dispersal from the Okavango into Namibia—what paths they use and what perils they face. We partnered with WWF Namibia to investigate this very issue, and Mandevu is helping us uncover one of the central questions. In June, we plan to start an extensive lion survey across the northern section of our study area—where Mandevu and his mate regrouped—in order to determine if there is a breeding population of lions there. We believe there is!

More updates on Mandevu and our survey will follow.