Botswana is renowned for its wild landscapes, epic wildlife, and its strong commitment to conservation. The country has set aside approximately 29% of its land area for conservation and is home to some of the world’s most iconic wildlife areas, including the Okavango Delta, Chobe National Park, Makgadikgadi Pans National Park, Central Kalahari Game Reserve, and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park.

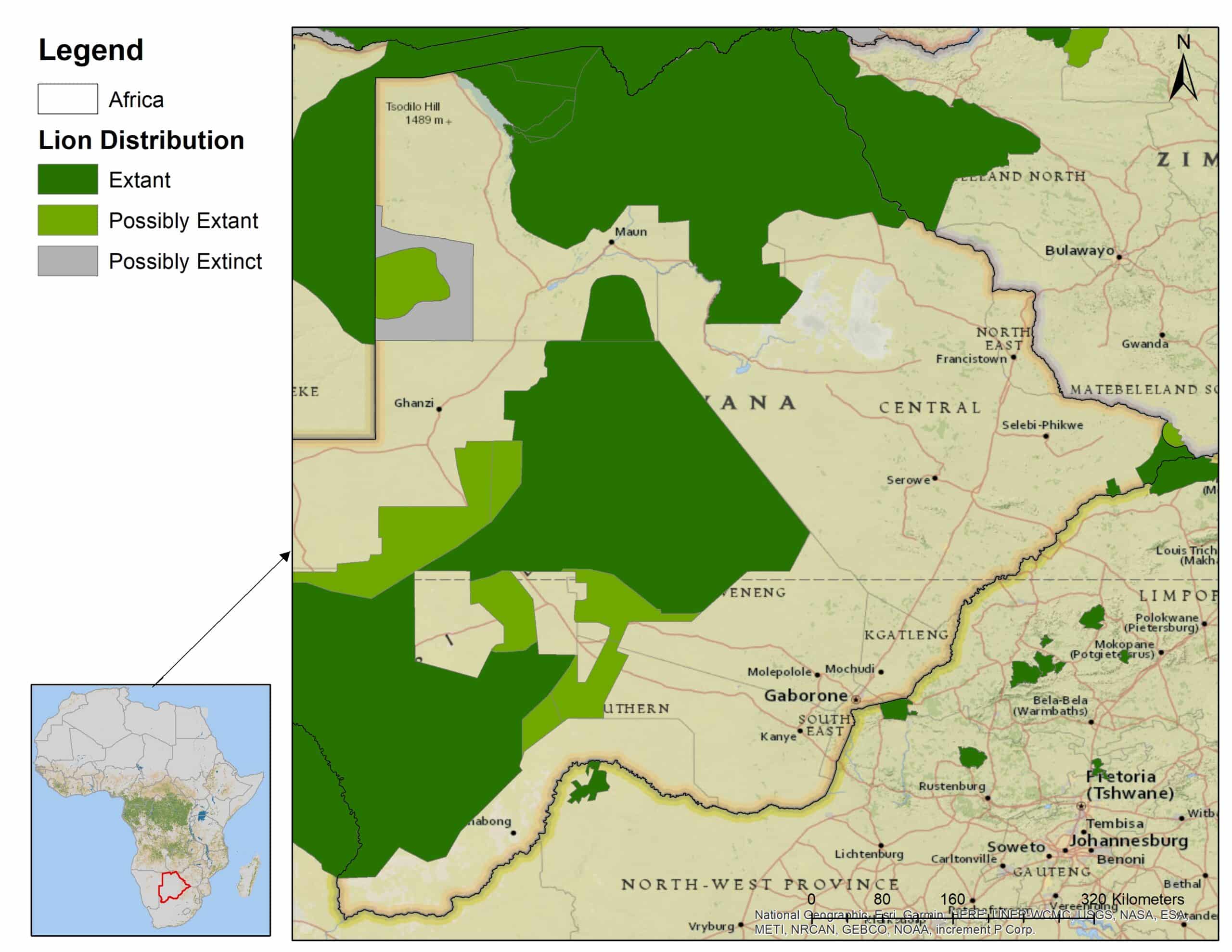

Botswana hosts the world’s largest population of elephants and the second largest population of lions, after Tanzania. A report compiled in 2015 by Christiaan Winterbach and Glyn Maude estimated that the national population of lions stood at around 3,500 individuals, with approximately 2,000 in northern Botswana, 700 in Central Kalahari Game Reserve, and 750 in the Kgalagadi. While these numbers are impressive, the general trend in Africa over recent years has been for numbers to be lower than expected when recounted, especially using more scientifically robust methods. There is no room for complacency, particularly given the growing human pressures on Botswana’s wildlife. There has been a gradual expansion of human and livestock populations in many of the country’s Wildlife Management Areas—a lesser category of protected area where multiple land uses are permitted. In addition, there is pressure on wildlife from poachers in search of bushmeat and body parts.

In February 2023, I visited Botswana to meet up with some of the organisations that the Lion Recovery Fund (LRF) is supporting. A big part of my work as Director of the LRF is to visit conservation projects to see if it makes sense to invest, and if so, how best to do so. In Botswana, the LRF is supporting several organisations, mainly to help tackle human-lion conflict and to promote coexistence between people and lions. We support CLAWS Conservancy and Wildcru in northern Botswana, we support Cheetah Conservation Botswana (who are working to retain connectivity between Central Kalahari Game Reserve and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park) in the Kalahari region, and we support Kalahari Research & Conservation in the Kgalagadi region in the south. The primary purpose of my trip was to spend time with Kalahari Research & Conservation as their existing grant had expired and they wanted to reapply to the LRF for further funding.

I landed in Maun—the gateway to the Okavango—to meet with representatives from Wildcru and Botswana Predator Conservation Trust. The next day, I was collected by Kalahari Research & Conservation’s Field Logistics Coordinator, Mmoloki Keiteretse. The plan was to drive through Central Kalahari Game Reserve to the western side, where we would visit Cheetah Conservation Botswana, before heading down to the Kgalagadi to check out Kalahari Research & Conservation’s field operations. We heard word of massive rains in Central Kalahari Game Reserve, with part of the Reserve receiving nearly eight inches in 24 hours. This meant there was a real risk of us getting stuck in one of Africa’s most remote landscapes. However, Mmoloki is highly experienced at working in Central Kalahari Game Reserve and was totally confident that the roads we planned to use would be safe to travel on.

Central Kalahari Game Reserve is massive, and at over 20,000 sq. miles, it is 7.6 times larger than Yellowstone National Park. We entered from the eastern side and drove into Deception Pan, the area made famous by Mark and Delia Owen’s book, Cry of the Kalahari. The Reserve looked absolutely stunning due to the rains, and though we had to drive through countless huge puddles, we didn’t come close to getting stuck. But we did come across a hapless couple from South Africa who had been stuck in the mud for three days. The look of relief on their faces when we managed to pull them out of the mud with our winch was priceless.

On the way into Central Kalahari Game Reserve, we saw large numbers of elephants along the veterinary fence line and multiple spots where they had broken through. To an outsider, the notion of jeopardising the country’s priceless wildlife assets by constructing fences that inhibit the mobility of wild animals to satisfy the European Union rules for beef imports seems hard to fathom. In addition to the ecological impact of those fences, the costs and effort needed to maintain them with such large numbers of elephants must be enormous.

In the Reserve, we were blessed to see big herds of oryx and springbok, numerous steenbok, and occasional sightings of hartebeest, giraffe, and wildebeest. The most notable sighting, however, was of a big male leopard who had stashed a springbok kill in a tree. He guarded this carcass for 36 hours at a site close to our campsite, giving us ample opportunity to view him before he was relieved of his kill by a pride of lions. A big lioness climbed the tree and chased the leopard away, only to drop the carcass. A big male lion then immediately grabbed the kill and proceeded to hog it, snarling viciously at any of the lionesses who dared come near.

After two days of exploring the vastness of Central Kalahari Game Reserve, we exited the Reserve to the west and visited Cheetah Conservation Botswana. Their cheetah work is focussed mainly on the commercial ranches of the Ghanzi District, but they are also doing important landscape conservation work in the GH10 and 11 Wildlife Management Areas that link the Central Kalahari Game Reserve ecosystem with the Kgalagadi ecosystem to the south. These interventions are as important for lions as they are for cheetahs. From there, we drove south to the small town of Hukuntsi, where I met other members of the Kalahari Research & Conservation team, including their two chief staff members, Dr. Glyn Maude and Dr. Moses Selabatso. We also met with Damien Mander from Akashinga, an NGO who is partnering with Kalahari Research & Conservation to strengthen conservation efforts in the area.

Kalahari Research & Conservation are working in the vast KD1&2 Wildlife Management Areas that border the 11,500 sq. mile Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park that straddles the border of Botswana and South Africa. The Wildlife Management Areas around the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park constitute critical wildlife habitat in their own right, and also provide a crucial buffer to the park. The main threats to wildlife in the Wildlife Management Areas are the expansion of the livestock industry and poaching of wildlife for meat. More boreholes are being drilled or opened up in parts of the Wildlife Management Areas, which is enabling livestock and people to gradually move further into the wildlife area. This creates competition for the limited grazing and also exposes wildlife to more pressure from poaching for meat.

Kalahari Research & Conservation are working with the local communities in KD1&2 to undertake land use planning to ensure that some separation is reserved between livestock and wildlife, and to limit the unplanned proliferation of livestock production in the Wildlife Management Areas, noting that those areas were set aside primarily for conservation purposes. Thankfully, many local people are supportive of wildlife conservation efforts, and the Basarwa (bushmen or Koisan) people in particular are keen to pursue wildlife-based livelihood options. Kalahari Research & Conservation have worked with the communities to develop a ‘performance payments’ system, where local people have signed a conservation contract that outlines the limits of the livestock grazing area. Using camera trapping and tracking, Kalahari Research & Conservation then measures the extent to which the grazing limits are respected and then pay the community performance payments based on the degree of adherence to the agreement. In addition, Kalahari Research & Conservation is working with communities to tackle human-carnivore conflict and reduce the costs borne by local people as a result of living with wildlife.

The partnership between Kalahari Research & Conservation and Akashinga will result in significant additional investment in the area. In the near future, this partnership will help to deter poaching for bushmeat and also introduce comprehensive community engagement programmes. These programmes will be designed to create nature-based employment, promote women’s empowerment, and strengthen health and education services. Through these efforts, the wildlife potential of KD1&2 will be retained, while improving the standard of living for local people.

The Kgalagadi landscape is epic. We drove for days through the vast, parched landscape to get a feel for the area and understand how best to support conservation efforts. In contrast to Central Kalahari Game Reserve, the Kgalagadi system had received disappointing amounts of rain, leaving the vegetation tinder-dry. Largely waterless for most of the year, animals in the Kgalagadi mainly survive without drinking. This includes the lions, who derive the moisture they need from dew and from the blood of their prey. The lions have become accustomed to visiting campsites in the Kgalagadi to search for water in the showers, or to lap up dew on the sides of tents. The Kalahari Research & Conservation team told harrowing tales of lying asleep in tents with lions licking the canvas inches from their face, and so every night we went to sleep slightly nervous that we would get a visit during the night. True to form, one evening we drove into camp to see an enormous male lion lurking by my tent, and we spotted another huge male in a shower. Camping in the Kgalagadi is not for the faint-hearted.

The Kalahari lions are magnificent beasts. Some individuals appear to be bigger than the lions in other parts of Africa, and the males often sport luxurious manes due to the cold Kalahari winters. The Kgalagadi ecosystem supports a significant population of lions, and on my visit we bumped into them four times. My visit to the landscape cemented the importance of investing in this epic wilderness. Though vast and wild, the Kgalagadi is fragile and threatened, and cannot be taken for granted. However, local communities are receptive to working with conservation groups towards a future where people and wildlife can coexist and thrive. We agreed that Kalahari Research & Conservation would apply to the LRF for further funding to support their performance payments system to allow for monitoring and protection of the lion population. Every cent invested in the Kalahari Research & Conservation/Akashinga partnership will result in the unlocking of 1:1 matching funds, meaning our planned investment of $200,000 will result in $400,000 reaching the ground to support the conservation of Africa’s famous Kalahari lions.